Licences#

Concerning IP in software-related fields, developers are likely aware of two “open” copyright licence categories: one for highly structured work (e.g. software), and the other for general content (e.g. Data including prosaic text and images). These two categories needed to exist separately to solve problems unique to their domains, and thus were not designed to be compatible. A particular piece of work is expected to fall into just one category, not both.

Copyright for ML Models, however, is more nuanced.

Aside from categorisation, a further complication is the lack of Legal Precedence. A licence is not necessarily automatically legally binding – it may be incompatible with existing laws. Furthermore, in an increasingly global workplace, it may be unclear which country’s laws should be applicable in a particular case.

Finally, licence terms disclaiming warranty/liability are contributing to an Accountability Crisis.

ML Models#

A working model is defined partially in code (architecture & training regimen) and partially by its parameters (trained weights, i.e. a list of numbers). The latter is implicitly defined by the training data (often mixed media). One could therefore argue that models must be simultaneously bound by multiple licences for multiple different domains. Such licences were not designed to work simultaneously, and may not even be compatible.

Here’s a summary of the usage restrictions around some popular models (in descending order of real-world output quality as measured by us):

Model |

Weights |

Training Data |

Output |

|---|---|---|---|

🔴 unavailable |

🔴 unavailable |

🟢 user has full ownership |

|

🔴 unavailable |

🔴 unavailable |

🟡 commercial use permitted |

|

🟢 open source |

🔴 unavailable |

🔴 no commercial use |

|

🟢 open source |

🔴 unavailable |

🟡 commercial use permitted |

|

🟢 open source |

🔴 unavailable |

🔴 no commercial use |

|

🟢 open source |

🔴 unavailable |

🟡 commercial use permitted |

|

🟢 open source |

🟢 available |

🟢 user has full ownership |

|

🟢 open source |

🟢 available |

🟢 user has full ownership |

|

🟢 open source |

🔴 unavailable |

🟡 commercial use permitted |

|

🟢 open source |

🔴 unavailable |

🟢 user has full ownership |

Feedback

Is the table above outdated or missing an important model? Let us know in the comments below, or open a pull request!

Just a few weeks after some said “the golden age of open […] AI is coming to an end” [14], things like Falcon’s Apache-2.0 relicensing [15] and the LLaMA-2 community licence [16] were announced (both permitting commercial use), completely changing the landscape.

Some interesting observations currently:

Pre-trained model weights are typically not closely guarded

Generated outputs often are usable commercially, but with conditions (no full copyrights granted)

Training data is seldom available

honourable exceptions are OpenAssistant (which promises that data will be released under

CC-BY-4.0but confusingly appears already released underApache-2.0) and RWKV (which provides both brief and more detailed guidance)

Licences are increasingly being recognised as important, and are even mentioned in some online leaderboards such as Chatbot Arena.

Data#

As briefly alluded to, data and code are often each covered by their own licence categories – but there may be conflicts when these two overlap. For example, pre-trained weights are a product of both code and data. This means one licence intended for non-code work (i.e. data) and another licence intended for code (i.e. model architectures) must simultaneously apply to the weights. This may be problematic or even nonsensical.

Feedback

If you know of any legal precedence in conflicting multi-licence cases, please let us know in the comments below!

Meaning of “Open”#

“Open” could refer to “open licences” or “open source (code)”. Using the word “open” on its own is (perhaps deliberately) ambiguous [17].

From a legal (licencing) perspective, “open” means (after legally obtaining the IP) no additional permission/payment is needed to use, make modifications to, & share the IP [18, 19]. However, there are 3 subcategories of such “open” licences as per Table 2. Meanwhile, from a software perspective, there is only one meaning of “open”: the source code is available.

Subcategory |

Conditions |

Licence examples |

|---|---|---|

Minimum required by law (so technically not a licence) |

||

Cite the original author(s) by name |

||

Derivatives use the same licence |

Choosing an Open Source Licence #

Software: compare 8 popular licences

MPL-2.0is noteworthy, as it combines the permissiveness & compatibility ofApache-2.0with a very weak (file-level) copyleft version ofLGPL-3.0-or-later.MPL-2.0is thus usually categorised as permissive [20].

Data & media: one of the 3

CClicences from the table aboveHardware: one of the

CERN-OHL-2.0licencesMore choices: compare dozens of licences

One big problem is enforcing licence conditions (especially of copyleft or even more restrictive licences), particularly in an open-source-centric climate with potentially billions of infringing users. It is a necessary condition of a law that it should be enforceable [21], which is infeasible with most current software [22, 23, 24].

National vs International Laws#

Copyright Exceptions#

A further complication is the concept of “fair use” and “fair dealing” in some countries – as well as international limitations [25] – which may override licence terms as well as copyright in general [26, 27, 28].

In practice, even legal teams often refuse to give advice [29], though it appears that copyright law is rarely enforced if there is no significant commercial gain/loss due to infringement.

Obligation or Discrimination#

Organisations may also try to discriminate between countries even when not legally obliged to do so. For instance, OpenAI does not provide services to some countries [30], and it is unclear whether this is legally, politically, or financially motivated.

Legal Precedence#

“Open” licences often mean “can be used without a fee, provided some conditions are met”. In turn, users might presume that the authors do not expect to make much direct profit. In a capitalist society, such a disinterest in monetary gain might be mistaken as a disinterest in everything else, including enforcing the “provided some conditions are met” clause. Users might ignore the “conditions” in the hope that the authors will not notice, or will not have the time, inclination, nor money to pursue legal action. As a result, it is rare for a licence to be “tested” (i.e. debated and upheld, thus giving it legal weight) in a court of law.

Only rare cases involving lots of money or large organisations go to court [24], such as these ongoing ones destined to produce “landmark” rulings:

Accountability Crisis#

Of the 100+ licences approved by the Open Source Initiative [34], none provide any warranty or liability. In fact, all expressly disclaim warranty/liability (apart from MS-PL and MS-RL, which don’t expressly mention liability).

This means a nefarious or profiteering organisation could release poor quality or malicious code under an ostensibly welcoming open source licence, but in practice abuse the licence terms to disown any responsibility or accountability. Users and consumers may unwittingly trust fundamentally untrustworthy sources.

To combat this, the EU proposed cybersecurity legislation in Sep 2022: the Cyber Resilient Act (CRA) [35] and Product Liability Act (PLA) [36] propose to hold profiteering companies accountable (via “consumer interests” and “safety & liability” of products/services), so that anyone making (in)direct profit cannot hide behind “NO WARRANTY” licence clauses [24]. Debate is ongoing, particularly over the CRA’s Article 16, which states that a “person, other than [manufacturer/importer/distributor, who makes] a substantial modification of [a software product] shall be considered a manufacturer” [37]. FOSS organisations have questioned whether liability can traverse the dependency graph, and what minor indirect profit-making is exempt [38, 39, 40].

However, law-makers should be careful to limit the scope of any FOSS exemptions to prevent commercial abuse/loopholes [24, 37], and encourage accountability for critical infrastructure [23].

Future#

To recap:

It’s unknown what are the implications of multiple licences with conflicting terms (e.g. models inheriting both code & data licences)

there is little Legal Precedence

“Open” could refer to code/source or to licence (so is ambiguous without further information)

training data is often not open source

Licences always disclaim warranty/liability

Enforcing licences might be illegal

Enforcing licences might be infeasible

there are ongoing cases regarding (ab)use of various subcategories of IP: copyright (no licence) for both open and closed source, as well as licences with copyleft or non-commercial clauses

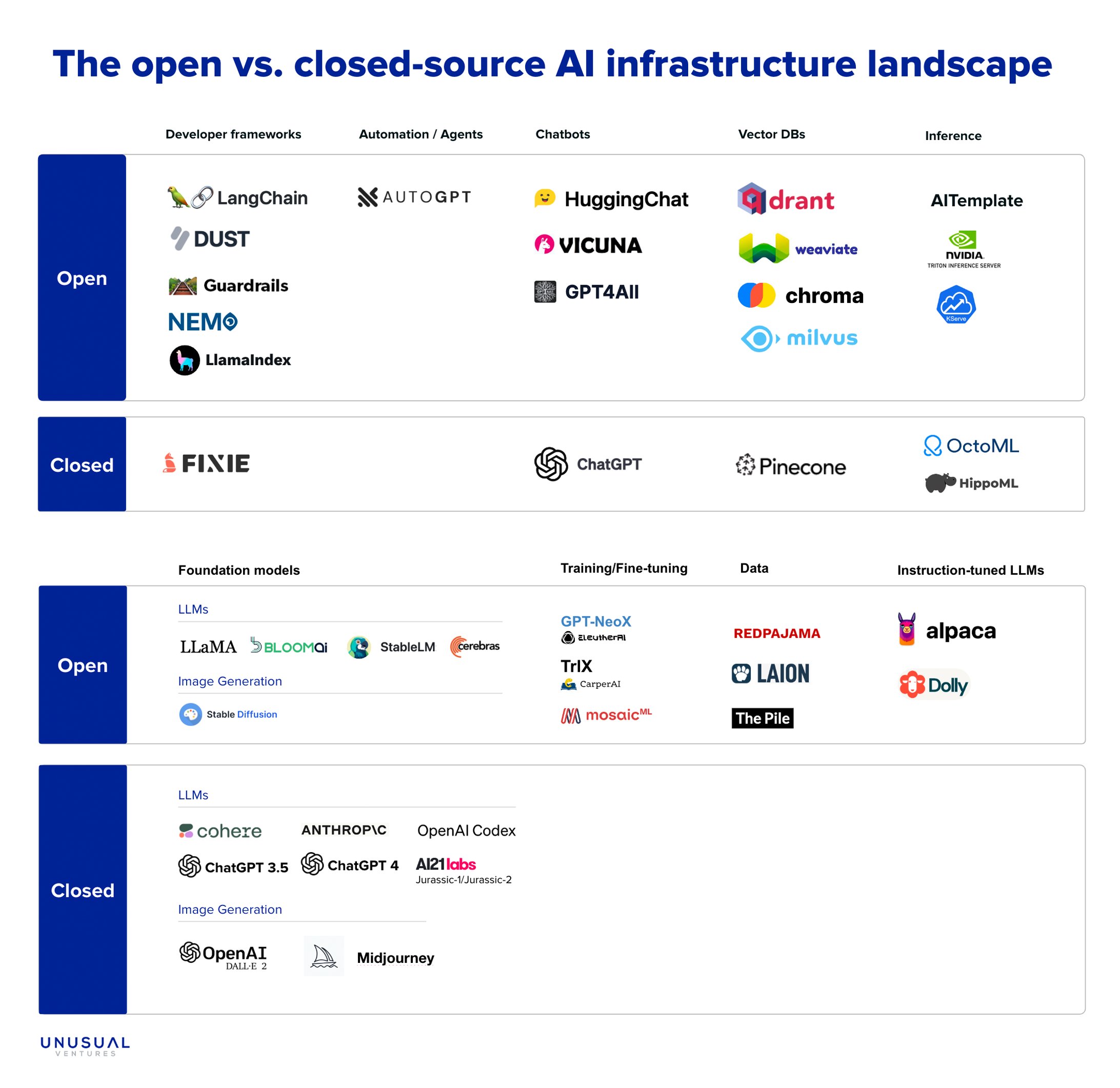

In the long term, we look forward to the outcomes of the US cases and EU proposals. Meanwhile in the short term, a recent tweet (Fig. 2) classified some current & foundation models (albeit with no explanation/discussion yet as of Oct 2023). We hope to see an accompanying write-up soon!

Feedback

Missing something important? Let us know in the comments below, or open a pull request!